Michelangelo Lovelace, “Art Saved My Life”

- Democracy Chain

- 6 hours ago

- 5 min read

by Lynn Trimble

ASU Art Museum, Tempe, Arizona

Continuing through February 15, 2026

The streets of Cleveland burst to life in paintings by Michelangelo Lovelace (1960-2021), a self-taught artist who professed that “art saved my life.” It was a keen observation, reflecting on the experiences he had growing up in the city he captured with loose, textured marks in bright colors that convey a vibrant kinetic energy.

This first retrospective survey of his work, organized by the Akron Art Museum, embodies themes that resonate in the current political climate, from racism to community care. Lovelace paints the best and worst of us, informed by his own experiences as a Black man living in an urban ecosystem where faith and joy intersect with danger and despair.

The exhibition fills three galleries, each with a different focus, an approach that equips us to expand our understanding of the artist’s identity and intentions. Before entering the first gallery, where most of the works highlight social injustice and are hung on bright red walls (the first of three primary colors used as backdrops, a nod to the role of art in Lovelace’s personal journey), viewers encounter introductory text highlighting the artist’s biography. Most notably, it recounts Lovelace’s own memories of drawing in earnest as a 19-year-old arrested for marijuana possession. The judge before whom he appeared asked what he was good at, suggesting that he turn to that if he wanted to avoid future encounters with the law.

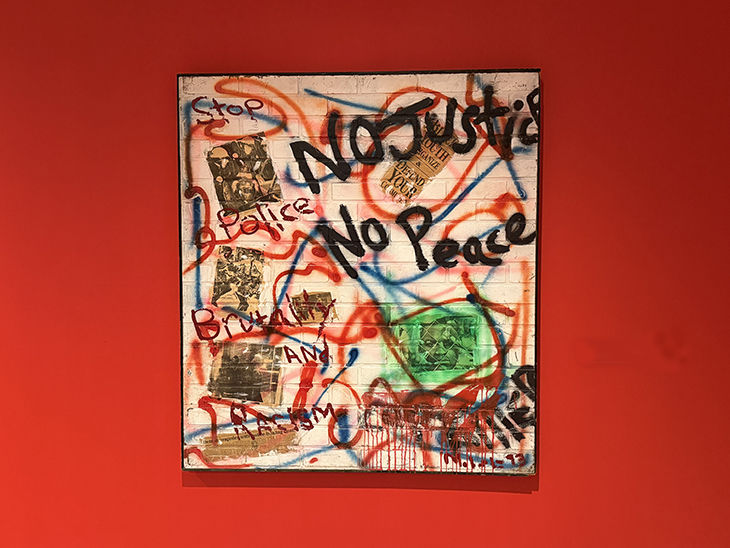

Painted between 1991 and 1993, a series of mixed media on wood paintings with collaged text and imagery are distinguished by their brick-like-texture, graffiti influences, and frames bearing the artist’s marks. For the “Rodney King Series” Lovelace embedded newspaper clippings and found photographs in works addressing the high-profile case of police brutality and community uprisings in Los Angeles.

Police vehicles and uniformed officers appear often in Lovelace’s work, but these pieces in particular punctuate the ways violence against Black bodies intersects with law enforcement. With “Crips & Bloods” (1993), Lovelace counters stereotypes of so-called Black-on-Black crime with themes of Black love and solidarity. With “Amerikkkan Just-us” (1992), the artist calls out the white supremacy and racial disparities that the dominant culture calls “the criminal justice system.”

Lovelace documents specific acts of injustice, speaking to the experiences of individuals and communities, but also to the wider systems undergirding them. We can follow Lovelace painting his way through his own life, but also diving into the social, economic, and cultural issues of the day. While drawing us into a particular time and place, the artist prompts us to consider our own life and times and our complicity in perpetuating cycles of poverty, war, and addiction.

In Lovelace’s “City Paintings,” such as “40th and Hood” (1994) and “Block Party” (2018), color and movement explode in scenes of people across generations and cultures taking part in the daily activities, from shopping to dancing, that bring them out into the street. But he also explores tragic themes, such as the school shooting depicted in “Streetology” (1999). Many of these works are mounted on blue walls, a color associated not only with the wide-open sky but also with the trappings of law enforcement. Considered with the red walls of the nearby gallery, they reinforce the sense that Lovelace essentially created an illustration of modern-day America, with all its complexities and contradictions.

Lovelace makes generous use of text, a choice rooted in the prevalence of signs and billboards in his urban environment. The approach allows him to insert phrases he finds meaningful and powerful, ranging from excerpts from the Bible or the Constitution to slogans such as “Black Lives Matter.” Likewise, roadways figure prominently in his city-themed works, where they sometimes appear as unifying factors in community spaces and other times as dividing lines. Where these roads lead, or whether it’s even possible to escape these city streets, isn’t clear, and the pictures are better for it.

Even as Lovelace tackles racism, he also prompts reflection on the specter of sexism and misogyny in both art and society. Women with babies and signs advertising sites of sexualized performance abound on the city streets he brings to life in acrylic on canvas, alluding to the Madonna-whore complex that runs throughout so much of art history.

“Genesis” (2018) features Black subjects while quoting “The Creation of Adam,” painted by the 16th-century Italian Renaissance master whose name Lovelace adopted early in his art career. That same year Lovelace also drew on popular culture with his caped “Black Super Man” (2018) as a counter to the white savior complex.

Among the works curated into the final gallery are several inspired by topical news events, such as Hurricane Katrina and the Covid-19 pandemic. Dozens of pairs of eyes peer out from a brick wall in “The Deportation of 11 Million Immigrants” (2016), one of the most powerful works in the show by virtue of the borderland issues impacting the region where it’s being exhibited and the broader spectrum of terror currently being waged against immigrants by the Trump administration in targeted communities.

Works mounted on a bright yellow wall, many containing American flag iconography but with stripes that run vertically like prison bars, speak to the intersections of racism and patriotism. In some works Lovelace sets people in front of these bars rather than behind them. Works referencing post-9/11 warfare, including “What Happened to World Peace?” (2001) and “Casualties of War” (2003) examine the local and global impact of America’s military-industrial complex.

“Art Saved My Life” reveals how Lovelace’s oeuvre ranges from hyper-individual to global. The large narrative scope he is able to address is juxtaposed with a group of intimate portraits drawn using marker, pen, or colored pencil on paper (primarily in 1993) which depict people Lovelace encountered in the rehabilitation unit of a medical center where he worked. Mounted on a bright pink modular wall, they suggest this was a setting where the artist found great joy in the midst of hardship. Lovelace’s own humanity, with its deep connections to artmaking, is the focus of five paintings anchored by “Self-Portrait” (1996), which depicts Lovelace reading a book by a window overlooking the city.

The roughly thirty years covered by “Art Saved My Life” lends significant insight into the creative impulses and life experiences that Lovelace channeled into vibrant explorations of personal and collective histories and expressive critiques of social injustice.

Lynn Trimble is a Phoenix-based art writer whose work ranges from arts reporting to arts criticism. During a freelance writing career spanning more than two decades, over 1,000 of her articles exploring arts and culture have been published in magazine, newspaper and online formats. Follow her work on Twitter @ArtMuser or Instagram @artmusingsaz.

Comments